- Home

- Linda Cracknell

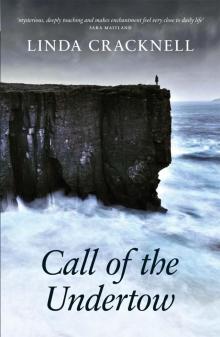

Call of the Undertow

Call of the Undertow Read online

CALL OF THE UNDERTOW

First published October 2013

Freight Books

49-53 Virginia Street

Glasgow, G1 1TS

www.freightbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Linda Cracknell 2013

The moral right of Linda Cracknell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without either prior permission in writing from the publisher or by licence, permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP.

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental

A CIP catalogue reference for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-908754-30-1

eISBN 978-1-908754-31-8

Typeset by Freight in Garamond

Printed and bound by Bell and Bain, Glasgow

For Phil

Linda Cracknell has published two collections of short stories, Life Drawing (Neil Wilson Publishing, 2000) and The Searching Glance (Salt, 2008). She writes drama for BBC Radio Four and edited the non-fiction anthology A Wilder Vein (Two Ravens, 2009). She received a Creative Scotland Award in 2007 for a collection of non-fiction essays in response to journeys on foot, Doubling Back (Freight, 2014). She teaches creative writing in workshops across Scotland and internationally and lives in Highland Perthshire.

CONTENTS

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY ONE

TWENTY TWO

Acknowledgements

ONE

When Maggie saw through the window that a snowman had appeared in her garden she put on wellies and strode out to face it, fist clenched against an impulse to punch its head off.

She prowled the garden, searching for clues in the blanket of snow that stretched the land even flatter on this bleak March day. From the trails, she could see that the intruders had rolled snow across the garden from her front gate. But she found no footsteps. She walked to the gateway and peered down the silenced lane, rutted with a single pair of tyre tracks. A newcomer still teetering on the edges of her own territory, she had no idea why anyone would sneak up on her like this.

She crept back inside and stood at one of three large windows in the sitting room, looking north to Dunnet Bay. She’d arrived two weeks ago to this place that seemed to scratch at her. Raw winds streamed past the windows carrying grains of ice or sand or both. The newspapers told of trucks lifted from harbour-sides by winter storms and smashed against walls. There was no shelter in the low-lying fields. Cattle, fenced in by flagstones processing like linear graveyards, hoisted their rumps into north-easterlies and sunk their heads. The strange abrasiveness had put her at ease; it suited her. It wasn’t an unfriendly place. No one passed her on the street without a greeting, but none of them had imposed further.

She glanced at the snowman. For what was supposed to be an empty place, there was now a sense that there could be people watching her.

From the window she looked through a lattice of bare branches outlining chinks of colour beyond. The effect was like leaded stained glass. She could just make out the jagged rise and fall of the dunes and beyond them a snippet of sea darkened by the nearby snow; the surf a yellowy-pink. No one lived between her and the sea. There was just a cluster of derelict farm buildings and birds that crashed their wings about in the gaunt trees; rooks’ nests perched in the dark filigree of topmost twigs.

She left the window, made coffee, and retreated to her study to settle to work. The phone jangled and she leapt to her feet.

‘How is it?’ she heard when she picked up the phone.

‘Good grief, Richard,’ she said, her breath ragged. ‘Isn’t it two months before you have to start harassing me about the atlas deadline?’

During the fortnight in which she’d been freelance and Richard had become her commissioning editor, he seemed to respond to her emails with phone calls, despite their habit of emailing when they’d been colleagues working at adjacent desks.

‘I meant life in wolf territory,’ he said.

She knew he was referring to Timothy Pont, an early mapmaker they both admired who’d been Minister of Dunnet Church, not far from her new home. In the late 16th century Pont had drawn sketch maps of the whole of Scotland which informed the earliest map of the country in Joan Blaeu’s monumental world atlas. Pont’s maps of the north coast showed vast white spaces into which only the capillary ends of rivers dared to penetrate; where no people seemed to be. ‘Extreem wildernes’ he had written across the white, and ‘verie great plenty of wolves doo haunt in this desert places’. Even now the road atlas didn’t make it look so different and had seemed to summon her here. To the white spaces on the map.

‘I’m surrounded by snow,’ she said.

‘Yikes.’

‘Don’t worry, there are daffodils coming up through it. Wolf territory is perfect,’ she said, trying not to think about the snowman.

‘Really?’

‘Yes.’

Backing off as he usually did when pushed, he updated her on office politics, upcoming conferences, his most recent trips to theatres, concerts and restaurants in Oxford.

‘They’re paying you too much for this job, aren’t they?’ she said, teasing him for his promotion.

‘Jealous, are we?’

That evening she locked the doors and checked the catches on windows thoroughly before going to bed. She slept like a sheepdog with one ear cocked. Her dreams were infiltrated by the still unfamiliar slips and shudders of the fridge, a rattle in a pipe, twigs cracking against a window. A wind rose up and howled around the edges of the house.

She got up early and went straight to one of the sitting room windows. The snowman had grown a luxuriant mop of dark hair. She went out, shoulders braced against an Arctic blast that grappled with her coat collar, and found the hair was fashioned from straggling lines of kelp. The snowman had grown a face too – a limpet shell for each eye, a razor shell for a long straight nose, and a curved gull feather for a smile. She stood scowling at it and then shuffled around her garden as she had the day before, head bent, hunting for tracks. She found none except her own.

She stood in her gateway to listen. Despite the cold, the birds were rioting in the trees nearby as if it was spring. Trills, cheeps, something that sounded like a mechanical clock being wound up, and a long sucking sound like a toothless great-aunt with a humbug. She had no idea which noises came from which birds. A tiny one had become familiar in recent days, calling her attention with its ‘chick-chack’ only to bob out of sight over the garden wall, flashing a white rear end.

Maggie’s landlady, Sally, appeared walking towards her up the snow-filled lane with her two boys, heading for their large bungalow a short distance beyond Flotsam Cottage.

‘Settling in okay?’ Sally smiled against the wind which carved away the flesh of her face and aged her by twenty years.

‘Surprised by this.’ Maggie indicated

the snow.

‘Winter’s last snarl,’ Sally said. ‘This time of year, just takes a puff of westerly and it’s away.’

Sally wore sheepskin mitts and in each one she held the hand of one of her two boys, hats pulled down over their ears. The children remained silent, kicking at the snow, and Maggie ignored them while she exchanged a few words with Sally about the cottage.

‘The boys like your snowman. Don’t you?’ Sally jiggled their hands.

They nodded, carried on kicking.

‘I didn’t... It wasn’t me,’ Maggie said, embarrassed at the implication that she would waste time on something so childish. She wondered briefly if it could have been these two who built it, but they seemed too disinterested somehow. ‘I don’t know where it came from.’

‘Really?’ Sally laughed. ‘A welcome from a well-wisher, perhaps.’

‘Perhaps,’ Maggie said.

‘And how’s the work going?’ Sally asked. ‘I’ve really no idea what a cartographer does.’

Maggie suspected Sally didn’t believe there was any work. No visitors arrived with briefcases; Maggie never went out dressed in a suit.

‘I mean are you off with gadgets and all that when you go out walking?’

Maggie laughed, explaining how the places she mapped were usually the other side of the world and she never even had to visit them. ‘I just like walking,’ she said. ‘That’s not work.’

Her walks so far had taken her half a mile to the village shop, from where she’d been making ever-increasing loops back home to get to know the area, charting it with her feet in her usual way. She observed oddities: roads that seemed fiercely silent were periodically tyrannised by boy-racer exhausts; a brown-harled beauty salon stood alone by the roadside; and on still days columns of steam plumed from the centre of the village. She noticed these things and then set them aside.

Sally looked thoughtful. ‘Callum’s doing a map-making project at school, aren’t you, love?’

The smaller of the two boys nodded.

Sally cocked her head down at Callum. ‘You might get some tips from Maggie, eh?’ The mother smiling at her child, cupping her hand on his head, pulling him into her side. ‘Maybe I’ll send you round.’ Sally looked up at Maggie and winked.

‘No, don’t,’ Maggie said, caught off-balance, her armpits flashing with heat. The child, Callum, poked a hole in the snow with his toe. But she’d also heard her own rudeness. ‘I mean, I’ve a lot of work on. I’m not sure I can help. Not at the moment.’

Sally tossed her head, her expression flickered briefly and then she smiled. ‘Don’t worry, I was only joking.’ She gathered the children up. ‘Well, boys, shall we go and get warm?’

They said their goodbyes. Maggie paused and turned to watch the three backs moving away from her along the lane towards their own door, half wanting to call them back and say something more friendly.

Back indoors she stood at a window glaring out at the snowman who’d ruffled her calm. She felt as if a handful of dark birds had been thrown up within her, thrashing beaks and wings against confining walls. Then they dropped to accept their earthbound trap, motionless except for the occasional blink of an eye.

TWO

Maggie had rented ‘Flotsam Cottage’, a single-storey steading conversion on the outskirts of the village, without viewing it. On a peninsula, practically an island, at a latitude of 58° 37’ 21”N, as far north as places with ice-names like Anchorage and Stavanger, the cottage had seemed right when she found it online and she’d signed a six-month lease – a long enough horizon for her to aim for.

In the days and weeks before moving she’d kept a road atlas open on the kitchen table and looked at it while eating breakfast. A road atlas, usually castigated by people like her for reducing landscape to a driver’s myopia, had been exactly right for her needs. She toured her eye around the profile of the peninsula, saw it as an animal head, perhaps a cat, with the nose raised at the north-east corner – Duncansby Head. To the south of Duncansby was the great yawning mouth of Sinclair Bay, toothless but opened wide as if in a scream, lined with a thin slice of yellow sand.

West of Duncansby was a round bear-like ear, before the back levelled away into smaller lumps and bumps towards Dunnet Bay, a soft and vulnerable indent with its wide strip of sand, a chink in the armour of what she took to be a rocky exterior.

The place names were enjoyable to say aloud; unfamiliar and sibilant. Sibster, Staxigoe, Slickly, Sordale. They sounded foreign – Skirza, Ulbster, Ackergill – left there by the Vikings probably, though from what she’d read, the Norse history of Caithness was forgotten now, only occasionally uncovered when sands shifted from a Viking burial site. The place names marched a set of characters fit for a children’s storybook into her head: Aukengill the herring; Murkle the mink; Rattar spoke for itself. The roads on the map, the blue branches of the rivers and tributaries, made lines along which characters might be drawn to each other and meet.

‘You’re mad,’ her sister Carol said when Maggie showed her the final page of the road atlas, the expanses of blank white paper, the few wiry roads and the tiny shaded areas indicating settlements. ‘Even I can read a map enough to see there’s nothing there. It’s not like you to be so remote.’

Instead of answering she randomly re-opened the atlas near the front; the South. Reading, Newbury, Basingstoke, Didcot, Southampton. The pages were a crazed circuit board of crossing wires - green or red for A roads, blue for motorways. Large shaded areas spoke of dense populations. Carol frowned at the atlas and Maggie closed it with a small thump; a strained line of understanding between them as usual. Carol, older by only two years at 42, even physically contradicted her sister: fair and curvy to Maggie’s darkness, height, crane-like angularity.

Maggie’s friend Helen was more polite. ‘I’ve never heard of it. Apart from that place of course.’ She poked a finger at John O’Groats, known as the most northerly point, even though the map clearly gave this role to Dunnet Head further to the west.

She bought a car, a second-hand Volvo.

‘You’re going to drive again?’ Carol’s tone now sweetened, sniffing her own agenda for Maggie of ‘getting back’ to something.

‘Easiest way to get there with my things,’ Maggie had said.

No one tried to stop her, but she sensed the whispered conversations, the concern. Helen offered her help with packing up. Even after Maggie had stopped attending the ‘Joining In’ community choir they’d both sung in, Helen and Maggie maintained their ritual of meeting for a coffee and bun at their favourite deli afterwards, the chat safely confined to weather, singing, buns. She also tried to put Maggie in touch with friends she said lived in the far north. She wasn’t the only one. They handed her pieces of paper with scribbled addresses and phone numbers. But the friends were usually in Inverness, a hundred miles away, or even Perth, two hundred. They were hardly going to be neighbours.

‘Does Frank know?’ Carol asked.

‘We’re not married anymore.’

‘I know,’ Carol said. ‘But.’

‘He knows.’

She packed essentials into the car and pointed it towards that far corner of the country, teeth gritted, radio up loud, crunching indigestion tablets; the first time she’d driven in two and a half years. Pulled north and north, with her left-behind self snapping at her heels but eventually dropping back and back, out-paced and shrinking as she passed Glasgow, the junctions thinning out, the land between settlements spreading. She stopped for a break in Pitlochry in the darkening afternoon, saw a hairdresser lolling and idle in her window, went in and had her dark hair cut short there and then. She barely looked at its effect on her face in the mirror, thought of it as a point of no return. Then beyond Inverness fewer and fewer villages with chains of orange street lights glowing out of the black and her breathing steadying. A road that rolled; a dark chasm now falling away to her right and one or two solitary ships’ lights out there in parallel journeys to her own.

; And finally the car had brought her to rest in these flat, open lands of the peninsula where there was nothing to hide behind. You could see so far; see your enemies coming. It was a relief to be so certain of her safety. That was, until the snowman had arrived in her garden.

Just as Sally promised, salt-laden winds turned the snow to slush, disappearing the snowman overnight except for a snowball left seeping into the grass. When the clocks changed at the end of the month, it seemed no warmer but the searing skies suddenly arced into long days, awaking a sort of hum in her and calling her beyond her established circuits.

‘You’ve been there a month and haven’t made a pilgrimage to Dunnet Church yet?’ Richard said at the end of a phone call one morning.

‘I’ve walked along the beach loads,’ she said. ‘But it’s really long. Dunnet’s the very far end of it. I’ve got work to do for some horrible boss, remember?’

Putting down the phone, she looked out of the window and saw the cold brightness of the day. Her deadline was still weeks away. She stood up and closed the laptop, pushed her bicycle past the car where it sat abandoned at its first resting place on the gravel driveway.

She pedalled towards the village passing the sentry-box beauty salon and a now familiar copse of tall, leafless trees amidst which shimmered a boarded-up church. A bit further along was a primary school. Then the village with its grey, squat cottages laid out on a grid of streets by a man who’d invented it from a quarry in the flagstone era – hence its name, Quarrytown. She had no notion of who might live in the cottages now. There appeared to be no source of employment other than the small commercial laundry behind the hotel that gushed out steam scented with a faint memory of Maggie’s grandmother. The streets often seemed empty except for tangles of boys and bicycles outside the chip shop or smokers leaning on the side wall of the hotel. Her visits to the shop had been an impersonal relief. Its window was chequered with notices for community events: a double glazing exhibition, a pipe band, some sort of crafts competition. Nothing of interest to her.

Call of the Undertow

Call of the Undertow